This site is not an official Fulbright Program site. The views expressed on this site are entirely mine and do not represent the views of the Fulbright Program, the U.S. Department of State or any of its partner organizations.

***

I feel like this post necessitates a brief preface, as it’s centered on a sensitive, potentially controversial topic (Korea vs. Japan). I want to emphasize that my analysis of the two cultures is not absolute, based only on my first-hand, personal experience living and traveling between the two countries. This is a sensitive topic for me too, and very personal… but I felt, after visiting Japan this summer, that I needed to work through some of the mixed feelings I was experiencing while traveling in Japan and upon returning to Korea. I wanted to share those reflections here with you in this newsletter, because I think that they fit well into the broader narrative I’ve been charting, of why I have chosen to spend a year abroad here, in Korea, and my intellectual identity as well. Some of these thoughts are perhaps not as joyfully positive about Korean culture as I would like them to be—but my experience in Korea hasn’t been all that pretty at times, either. These are my true, honest reflections, and I hope that you receive them with an open mind and heart.

***

I have long waited for an opportunity to return to Japan—so when I learned that Fulbright’s vacation policy stipulated that ETAs (English Teaching Assistants) would only be allowed to spend exactly 14 days abroad during the entire grant year, I knew I had to spend all 14 days… in Japan.

I first visited Japan in the spring of 2018, via a global education trip with my high school, which took a small cohort of students across the country to visit various kiln sites and cultural landmarks. I wrote about this trip for both my study abroad application in 2019 and my Fulbright application. It was a landmark experience, inspiring me to study Japanese (instead of Korean) in college, and sealing the fate of my aesthetic taste—a primal scene of sorts:

“The [Ryutagama ceramics] studio itself was beautiful… [and] we had visited in March, so the cherry blossoms had just begun to peal open to reveal beautiful, light-colored petals as light and transparent as tissue paper.” (2019)

“…I fell in love with the lush landscapes and artistic styles that were so different from what I had seen in Western art museums.” (2021)

Returning to Japan felt, in some backwards way (given my intentions for living in Korea this year) like a return to self. The city reminded me of things I loved and valued which I had been forced to suppress, because of how little ownership I have over my present lived environment, and because of my efforts to embrace the lifestyle of those most proximate to me now.

Little joys flowed abundantly in Japan—the sweet scent of incense perfuming narrow alleyways, the scant presence of cars and the prioritization of pedestrians and bicycles, vending machines, the (albeit annoying and sometimes stressful) preference for cash over card, the muffled Showa-era music crackling through the taxi radio, the sensation of my bare feet on wooden floors weathered smooth over the decades, the dingy record bars, the sharp scent of cedar, umeshu, and all the teas—the dizzying selection of chilled bitter teas in convenience stores, the teas at the beginning and end of nearly every meal, the rich cold-brew teas offered as a courtesy beverage in tea shops, and the myriad offerings of matcha and hojicha flavored sweets.

These little things made me happy—I felt as though my senses were finally reawakening after months of hibernation. As I (jokingly) told my friends in America, I had finally returned to the spiritual motherland.

Over the past few years, I have become increasingly self-conscious of how my appreciation for Japanese aesthetic and material culture, which feels so personal and precious to my own experience, is largely a byproduct of Orientalism, Japanese nationalism, and Japan’s aggressive exportation of its own culture. In my past trips to Japan, I have been mesmerized by the magic that seems to pulse through even the smallest pieces of paper packaging—a kind of kinesthetic vitality that I have not found elsewhere. But this time, I couldn’t help but wonder: how much of this charm is idiosyncratic to my personal aesthetic experience, and how much of it is just an illusion manufactured over decades of marketing? (As one New York tea man once told me, Japan is great at advertising.) How much of the Japan I thought I was seeing was actually real, and how much of it was what they just wanted me to see?

Traveling directly from South Korea to Japan, it is quite evident in the country’s infrastructure Japan developed more slowly and steadily than Korea. I think the transportation design in Japan is perhaps most emblematic of this—and not just the famous trains themselves. The stations in every city we visited (Tokyo, Kanazawa, Kyoto, Nara, Osaka) were elegant, elaborate structures, built to impress and intimidate, their spotlessly-clean floors lined with austere stone and glass ceilings slick, tasteful, and modern.

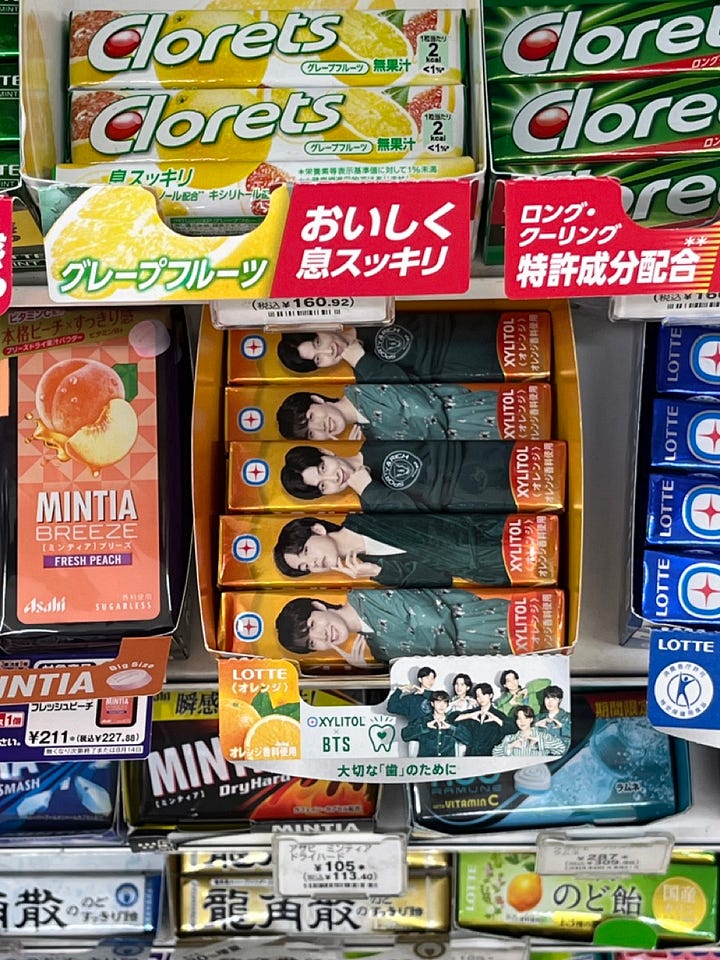

A friend who recently visited me in Korea, making a short weekend trip from Japan, observed that there is something about Seoul that feels very old—as though certain buildings and fixtures had not been updated in decades. The cityscape is a hodgepodge of different styles from the past sixty years, a mixture of old and new. Yet compared to Tokyo, a timeless behemoth, Seoul feels like a relatively young city, still thirsting with a desire to prove itself; perhaps the same could be said of Korea, too. The hottest new K-pop songs blast from speakers outside stores, florescent LEDs beat down upon you from all directions, and AC wafts out onto the street, beckoning you in with its cool capitalist promise. There are streets like this in Japan too (Dotombori in Osaka, Takeshita in Harajuku, Tokyo, and Shijo street in Kyoto), but in Korea, these streets are ubiquitous, present even in my big-little city of Gumi. This speaks to the marvel of Korea’s rapid development, but it also highlights the degree to which speed in Korea is often valued over enduring quality and beauty (a product of the “빨리 빨리” culture I have now grown much acquainted with).

Then, there are the entertainment gimmicks in Korea, from the drone show in Busan to the Banpo Bridge Moonlight Fountain Show along the Han River in Seoul, the cable cars, and the festivals for everything, from strawberries to mud. I have only visited a couple festivals here, but I felt that they were overcrowded and stocked with the Korean equivalent of fair food (although infinitely better than anything America could ever produce) and souvenir trinkets.

Traditional culture also gets swept up in this aggressive commercialization, too—hanoks in cities are often gutted and transformed into tourists attractions outfitted with tasteful cafes and shopping boutiques, untethered to the communities and individuals who once lived there (the area surrounding Insadong is emblematic of this). The sparse presence of older structures and neighborhoods in Korea and their subsequent gentrification is a sore reminder of how colonization and war interfered with the preservation of Korea’s traditional culture alongside its modern development. Many placards and tourist pamphlets in Korea will tell you that key heritage sites were burned down by the Japanese and rebuilt after the war.

Culture in Japan does not seem to be announced so explicitly as performance—rather, it is woven directly into the very fabric of the streets themselves. Small design motifs, such as the use of wood and the grey-black tiles lining the roofs of many buildings in Japan recall the facades of traditional structures, creating a uniform landscape that feels both vintage and modern. (There is evidently a concerted effort to imperceptibly create this homogeneity. Four years ago, while I was studying abroad in Kanazawa, a couple who owned a coffee shop I often frequented told me that there are strict regulations as to how high structures can be built in the city, and which colors shopkeepers are allowed to paint the exteriors of their businesses.) In a city like Kyoto, traditional machiya are also often transformed into shopping and eating districts, but these commercial areas exist alongside older structures that remain inhabited by locals or have been reconfigured into tea stores and antique shops, each a miniature museum of sorts.

Unlike the flashy storefronts of Korea, many shops in Japan seemed rather uninterested in soliciting business. Google Maps was useless about 40% of the time. There were many occasions in which my family tried to eat at a restaurant, only to find a handwritten note hastily scrawled and posted to the outside of the building indicating that it was closed. Sometimes, the door would be unlocked, and the owner would be doing a bit of paperwork inside. Navigating Japan often felt like trying to find a very exclusive speakeasy or secret society. If you’re in the community, you’re in the know, but otherwise, everything is very quiet.

Sometimes, particularly when I first arrived in Korea, I could not help but compare the two countries, seeking in vain the same feeling of awe I felt while in Japan. And time and time again, I found myself disappointed. I have a penchant for being unreasonably harsh on those who care about me and love me most (my family). Perhaps, as an Asian American, I have spent most of my life wishing that I could be something that I was not.

But this time, visiting Japan, I could see how so many of the things that I loved most about Japan were at least somewhat contingent on the wealth the country accumulated as a Western-imitative colonial power in the 20th century—and how so many of the things I was critical of in Korea were contingent on its war-torn history. I often think about a conversation I had with a fellow gyopo in Seoul—a friend of a friend of a friend, who had spontaneously decided to spend several months in Korea. We had been discussing some of the aesthetic differences between Korea and Japan, and perhaps sensing a slight distaste in my tone, he noted that he couldn’t help but feel a bit of respect and pride for how quickly Korea had been able to build itself back up following its independence.

I am proud of this, too—and I must admit that I am proud of the soft power Korea has accumulated for itself, and the desirability this has projected onto “Koreanness,” for I feel the waves of this (Hallyu, or the Korean wave) in America. Yet I am also disappointed by how much this recent development seems to be an act of mimicry—from the evolution of K-pop, initially inspired by the J-pop idol industry and largely indebted to rap and RnB, to the Korean appetite for big European cars and franchised fast food (fried chicken, burgers, and Subway sandwiches). Perhaps this inner critic is the Korean American in me—with some distance I am critical of the points that seem a little kitsch, yet as a Korean, I yearn for my kinland to define an aesthetic sensibility of its own.

Ironically, Korea’s openness to overseas influence is exactly what makes it possible for me to be here. While both Japan and Korea are considered monocultures, in the sense that a single set of beliefs, attitudes, and values belonging to one ethnic group dominate society, there seems to be greater degree of openness to foreigners here in Korea than in Japan. Japan has notoriously always been a bit distrustful of outsiders. Fulbright Japan only has six available slots for recent college graduates—all of them study-research grants that require a working proficiency of Japanese. This is pathetically small compared to the whopping eighty English Teaching Assistantships and fourteen study-research positions offered by Fulbright Korea. Foreigners who want to teach and work in Japan have other options—most notably, the Japan Exchange and Teaching, or JET, program—but unlike Fulbright, which is a special cultural exchange partnership between the U.S. government and nations around the world, the JET program is exclusively a Japanese government program. Even now, more than 150 years after the isolationist policy of the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan still remains guarded against the influence of outsiders. (My favorite piece of evidence is the Japanese language itself, which with three scripts—one of which requires memorizing over 2,000 Chinese-derived characters in order to be fluent by governmental standards—is 너무 너무 너무 difficult to learn if you did not grow up speaking it.)

I felt this skepticism on the ground while traveling in Japan, even as someone who is Japanese passing. I have never felt like I had to doubly explain to people in Korea what it means for me, someone who looks East Asian, to be American—on the contrary, I have found that I often need to fight for my right to even be considered Korean—but in Japan, even after I had explained that I was from America, people wanted to know where I had really come from.

During one of my final days in Kyoto, I decided to try an obanzai restaurant that had fairly decent reviews. The place was run by a Japanese obasan, perhaps in her sixties, and when I arrived, there were only four other customers: a couple that seemed Asian but not Japanese (it turned out that they were Australian), and an elderly man and woman, similar in age, who appeared friendly but not necessarily together (there was a courtesy seat padding the space between them). The obasan looked confused when I entered—maybe I also seemed a little disgruntled—and even more so when I opened my mouth and it became apparent that Japanese was not my first language.

Yet she took me in, perhaps out of obligation, seeing that I was alone. At some point, another couple poked their heads into the restaurant, and the obasan immediately ushered them back out into the street, exclaiming exasperatedly, “we’re full, we’re full”—despite the fact that more than half of the seats were still empty. The older Japanese lady customer asked, “They weren’t Japanese?” which the obasan affirmed, and the three of them—the two women and the man—laughed. Later on, when talking to me, she would say that the reason why she had shooed away the other guests was not because they were foreigners, but rather because she ran the restaurant by herself and could not have too many customers.

A couple months ago, I spoke to a friend of a friend about her experience teaching through the JET program. Although our conversation first focused on her teaching experience, I was curious to hear how she felt about Japanese culture itself, now that she was about to begin her third year of teaching. One of the very first things she mentioned was Japan’s wariness towards outsiders. Although she had been teaching at the same school for the past two years, not once had she been invited to a hwesik, or after-work dinner gathering (I was shocked to hear this, as I had already attended more than five at the time at my school in Korea). She also said that it was difficult, as an adult and a foreigner, to make new friends in Japan, as most people were closest with their friends from their middle school and high school days. Although Japanese people might be friendly with you, it would take a very long time before they would see you as more than just a close acquaintance.

I know that I will always be an outsider in Japan, and I know that my affinity for Japanese culture makes me a bit of an outsider in Korea, too (that’s the American in me)—and yet, I can’t control how I feel. Regardless of whether or not my perception of Japan is distorted by its soft power image, I know that the sensations and emotions I experience when I’m there are real.

When I first arrived in Korea, I think I was hoping to find something on the level of the sublime—a kind of magic that would rouse within me the same aesthetic thrill I experienced during my first trip to Japan nearly seven years ago. But Korea is not Japan, and despite my efforts to both understand and critique Orientalism as an undergrad, perhaps I had inadvertently made the Orientalist assumption that the shared cultural history between the two countries would be enough to create an overlap in aesthetic experience, as well. Instead, arriving in Korea, I was greeted by a culture that was a little too familiar and a little too garish for my liking.

Much to my chagrin, after spending two weeks in Japan, I found myself longing for some conveniences in Korea that I expected I would be able to find easily in Japan. I yearned for easy access to well-air-conditioned, beautifully designed cafes and coin noraebang. I missed using Naver Maps to find new restaurants, which I am now convinced is more intuitive and effective for searching than Google Maps. I wanted the affordability and convenience of calling a taxi with KakaoT. I missed the simplicity and ease of reading hangul, and I kept accidentally slipping into Korean whenever I tried to use my rusty Japanese. For all my misgivings and criticisms, I had grown accustomed to life in Korea.

A few weekends ago, I went up to Seoul to see a friend. It had been a while since I had properly explored the city. On Sunday, before I returned to Gumi, I had a bit of time to myself and decided to walk around Myeongdong in the area near our hotel. It was early afternoon, and the streets were swollen with throngs of Korean families and couples enjoying the last remnants of summer. As I wove through the crowds, I was overwhelmed by a strong sense of assuredness that I had never felt before. It was the feeling that for once, I knew that I deserved to be here, coupled with the awareness that those around me had no reason to suspect otherwise, either. (And even if they did, there was nothing they could do or say to change the way I felt, because I knew that it was in my birthright to be there.) It was a feeling of alignment between what I understood to be my inner and outer selves and my environment. It was a sensation that I would certainly never be able to experience in America, and would likely never experience in Japan, either.

I think some Americans perceive Korea to be a vain society. One of my friends, for instance, recently commented that Korean celebrities seem to post a disproportionate number of selfies of themselves on Instagram. And with the long-existing prejudice that beauty is frivolous, it is no wonder that Korea—known globally for K-pop, K-dramas, K-beauty, and plastic surgery—is seen as somewhat superficial. I think internally, I also believed this to be true as well (this was sort of one of the reasons why my family did not go to Korean church when I was young).

I have tried, with some success, to feel proud of contemporary Korean culture. But for all my mental gymnastics, after living here for the past eight months I cannot deny that contemporary Korean culture does feel superficial. There is an obsessive image-consciousness here that manifests perhaps most concretely in the mirrors that are absolutely everywhere—in the elevators, lining the sides of escalators, and in every single classroom at the middle school I teach at. Perhaps this is the greatest evidence of defeat for those of us who believe that there is more to beauty than just surface—for if my intuition is justified, then contemporary Korea is truly all glitter and no soul.

Yet I still retain the hope that there is something there—and I will continue to search for it, that ghost in the machine. I have to believe this—as a Korean American, it is the only way forward.

Such a thoughtful and thought-provoking reflection deserves a much larger audience. Would it be all right if I linked this post to my FB account? I think Fulbright also has spots for folks to post. So many memories came flooding back while reading this. I participated in a Fulbright teacher exchange in Germany. While I could pass for German (many Germans were convinced I was Austrian,) I never “felt” German. Each interaction was a mini-performance to see if I could “be” German. Success and failure followed. Many of the fails were hilarious. I also reflected on my Israel Fulbright. More stories…..lots of them. Thank you for your insightful, deep observations and sharing your cultural experiences. Both Korea and Japan seem more understandable after reading your writing. Safe travels!